In an era when Canadian furniture manufacturers were struggling to compete with international imports, one company stood out not just for its elegant craftsmanship but for the remarkable story behind its founder.

Craftline Industries, established in Toronto during the mid-20th century, was the brainchild of Manny Drukier, a Holocaust survivor whose vision, ingenuity, and resilience transformed a fledgling furniture operation into one of Canada’s premier producers of home furnishings and decorative clocks. With little formal education but a boundless entrepreneurial spirit, Drukier built more than a business—he created a legacy that continues to tick away in homes across North America.

In preparation for an article on Craftline Industries and its founder, Manny Drukier, I contacted the Drukier family with a series of questions. My main point of contact for this article was Cindy Drukier, Manny’s daughter. The Drukier family responded with remarkable generosity, providing a wealth of information, far exceeding what I had initially sought. I have included the entire text of their reply to me and have their permission to make minor edits for flow and clarity.

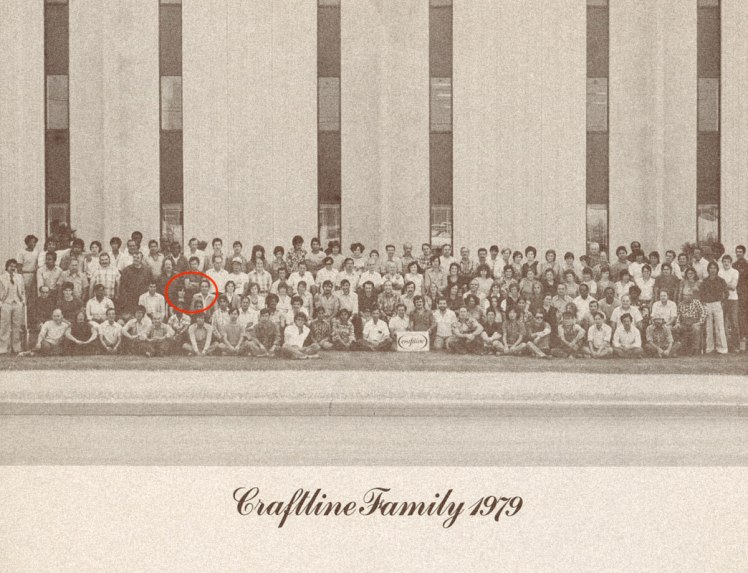

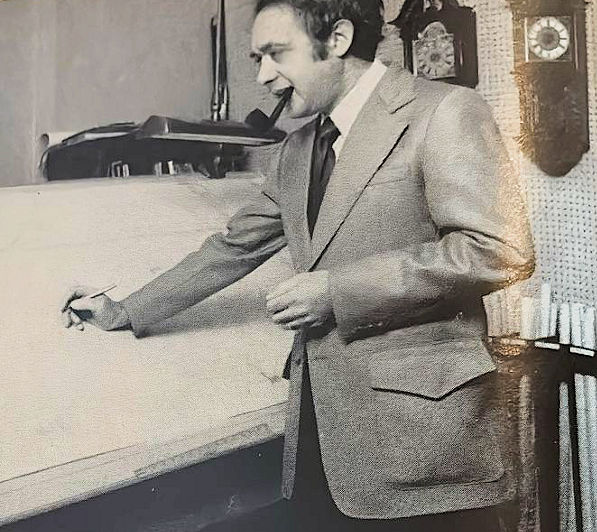

A snapshot of production, entitled Production Operations 1974, offers readers a clear sense of the scale and ambition behind Manny Drukier’s vision.

Manny Drukier’s Story as Told by His Family

From his daughter, Cindy Drukier, “The answers to the questions you asked may be more than you bargained for. Apologies for the excessive detail in some places, but the family decided that since such scant online evidence of Craftline exists, this was an opportunity to enter it into the digital record. These days, if it doesn’t exist online, it’s almost as if it never happened. So we’re grateful for the opportunity!”

The answers were written by Manny’s daughter Cindy, with input from her mom, Freda Drukier, and three siblings, Gordon, Laurie, and Wendy. Cindy also consulted the 1974 Canadian Jeweller article (which I have summarized in a separate section) and Manny’s unpublished writings. Manny has a published memoir, “Carved in Stone: Holocaust Years – A Boy’s Tale,” but it stops when he arrives in Canada. He wrote a Part 2, but it wasn’t published before he passed. Manny died in January 2022 of Alzheimer’s at 93.

The Vision

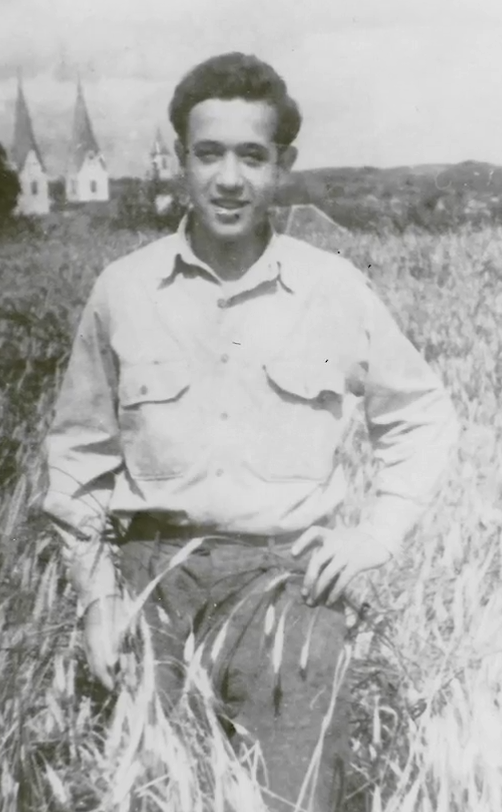

In 1948, Manny arrived in Toronto, a 19-year-old Holocaust survivor from Poland. He’d already spent a year in New York, but his mother and sister had made it to Toronto post-war, so he moved to Canada to join them.

Suddenly, Manny had to find a way to support the family. While buying furniture for their tiny flat with savings from New York, it dawned on him that the city was full of fresh immigrants needing to do the same—furniture would be a booming business, he figured. He had zero experience but managed to finagle (i.e., lie that he had experience) a sales position in a furniture store and quickly excelled at it, earning $30 for a six-day week, plus 2 percent commission.

He lasted less than a year working for someone else. By then he decided he had learned all he could and would go into business for himself.

He rented his first small store with his brother-in-law, David Rosenfeld, on Bloor St. West near Dufferin in downtown Toronto and called it North American Furniture. It went well, and soon they opened a second location on The Danforth on the east side of downtown Toronto. In 1961, they closed both to open a much larger and more upscale store in a former supermarket at Bathurst and Eglinton.

By 1964, he noticed he was importing more and more goods from the United States because Canadian furniture, although well-made, wasn’t elegant enough for modern consumer demand. He saw an opening in the market. He also disliked being the middleman—selling the wares of others—so he decided to go into manufacturing.

He didn’t have a clue how to do it, but he thrived on challenge and had infinite faith in his ability to figure things out. He sold North American Furniture to his brother-in-law and cobbled together a couple of partners for his new venture. Leonard Caplan was manufacturing case goods in Georgia, and Henry Gancman was a Canadian maker of chrome kitchen sets, which Manny sold in his store.

They opened a small factory in the north end of Toronto, on Lepage Ct., employing about 15 people. One was my mother, Freda, who set up the bookkeeping and ran the one-woman office.

A couple of years later they moved to a bigger location, that included a showroom, on Milvan Dr. A few years after that they bought some land (including some from the power company, Ontario Hydro), to eventually build a 215,000 sq foot factory, showroom, and offices on 13 acres located at 15 Fenmar Drive in Weston, and industrial area at the northwest end of Toronto.

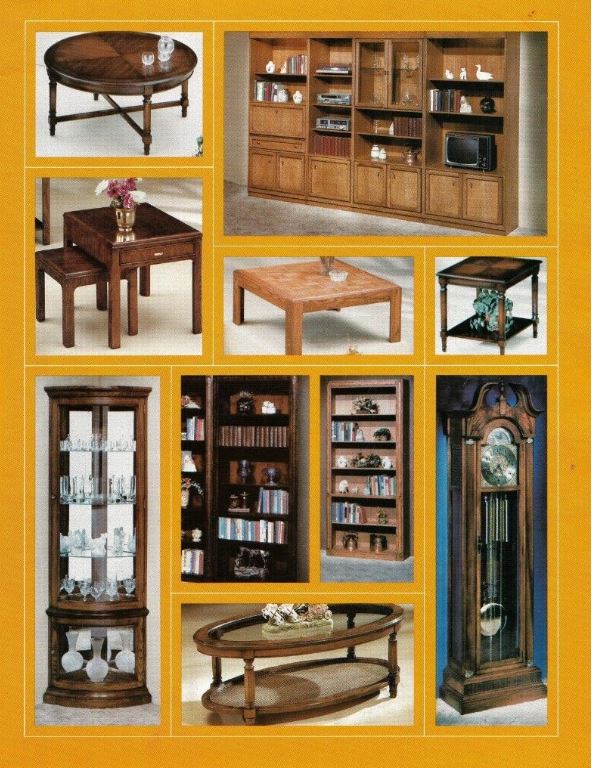

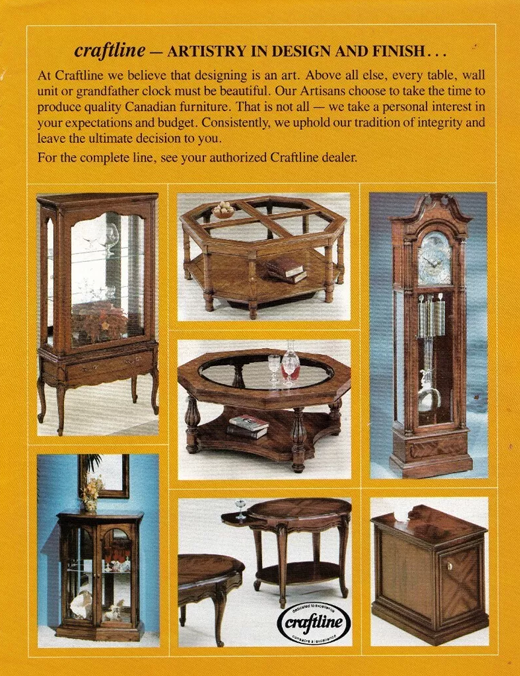

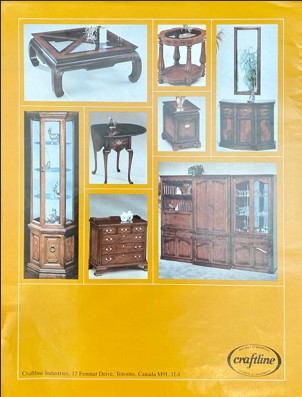

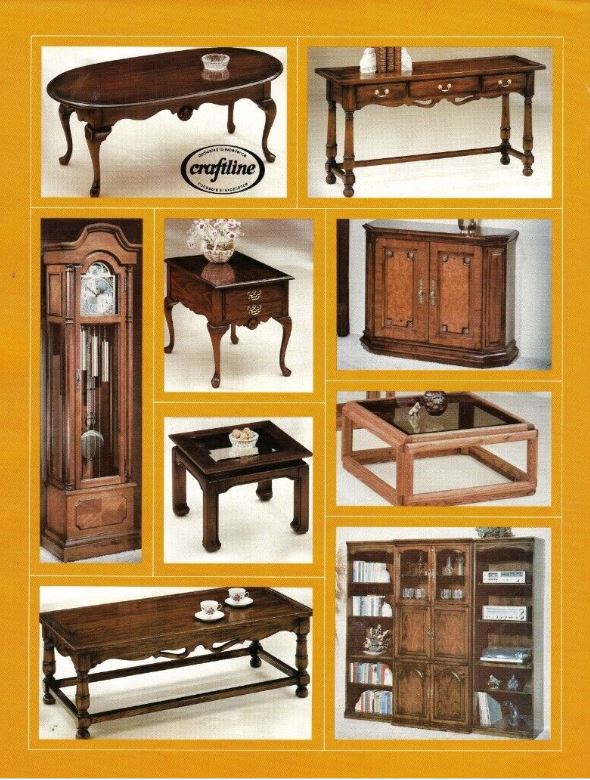

Craftline manufactured all-wood occasional furniture such as coffee tables, end tables, curios, and consoles, and, later on, wall units and grandfather and grandmother clocks. It eventually became Canada’s top manufacturer of elegant furniture, employing about 250 people.

Cindy added, “Manny was the main designer for all the furniture, including the clocks. He had no experience in this, of course, and couldn’t really draw on any either, but he always had lots of ideas!”

Production Operations 1974

The information in this section is sourced from the March 1974 issue of Canadian Jeweller magazine.

Demand for Craftline grandfather clocks was high in 1974—so high, in fact, that the company couldn’t keep up with orders. In 1973, Craftline produced 2,500 grandfather clocks and expected to double production by the end of the year, 1974. At the time, owner Manny Drukier estimated the U.S. retail market for clocks, priced between $200 and $4,000, to be worth $200 million.

Craftline began making grandfather clocks in 1968, and by 1974, 20% of the company’s total output was devoted to them. The tall clock cases were made from solid lumber and veneered with fruitwood, elm, and ash, in styles such as Spanish, Mediterranean, Colonial, and Country French.

They produced both eight-day mechanical clocks and transistorized, battery-operated, pulsation-type clocks. The higher-priced models used mechanical movements, while the less expensive versions, made by subsidiary Craftique, used battery-powered movements. Craftique, by 1974, had manufactured 14,000 units.

In 1974, clock faces, hands, and weights were imported, although Craftline was exploring Canadian sources. The mechanical movements were imported from two suppliers in Schwenningen, Germany. One supplier would have impacted production, while relying on two suppliers was a safer approach.

While the suppliers were not named in the article, at least six companies were manufacturing movements in Schwenningen at the time: Kienzle, Mauthe, Hermle, Schatz, Urgos, and Haller. (Author’s note: Urgos and Hermle would have been the suppliers)

Eaton department stores began selling Craftline clocks in 1972, but could not get enough stock to meet demand. However, most clocks were sold through furniture stores, where salespeople were well-equipped to market them. Jewellery stores typically bought in smaller volumes, as limited floor space made it harder to display the larger clocks.

The Craftline plant could finish 700 clock cases in two days, but the four-person team responsible for installing movements could only assemble 36 completed clocks per day. Much of the training for clock assembly was done in-house, with employees learning from one another.

Back to the story.

Launching the Clock Line

Manny constantly had an antenna up, looking for profitable ways to expand Craftline’s offerings, and, in 1968, he got the idea for grandfather clocks. We’re not sure where the idea came from.

Manufacturing the wood cabinets was easy, but not so the clockworks. He had two suppliers in the German Black Forest, but we don’t know more than that. I do know that, being a Holocaust survivor, he initially had misgivings about buying the works from Germany, but they were excellent and reliable, so he went with it. He said he also considered sourcing them from Asia, but decided it was too risky. He had expressed hope of buying them from a Canadian source in the future, but that never happened.

The clock cases were made of hardwood like elm, ash, and fruitwood. There were many designs, including traditional, Spanish, Mediterranean, colonial, and country French. They either had an eight-day wind-up chain mechanism or battery-operated pulsation movements. The highest-end grandfather clock was an oriental design with black lacquer and gold. The wholesale price for that clock was about $1,000 (CAD) in the early 1970s. It was the only model with an imported case—from Portugal, as it turns out.

He also started a spinoff company called Craftique Originals that produced ornamental objects from molded urethane. Craftique’s products included elaborate mirror frames, framed art reproductions, wall-mounted weather stations, and a line of wall clocks that looked like miniature grandfather clocks—except their brass weights were purely decorative and they didn’t chime.

Clock Sales and Ice Cream

Craftline had a team of salesmen who covered Canada coast to coast, and a bit of the eastern United States. All clocks were branded as either Craftline or Craftique, and they were sold to department stores and independent retailers, not to individual customers. He did, however, offer a premium service: customers could order a personalized engraved brass plate for their clock. Cindy Drukier spent one summer filing invoices and using an engraving machine to etch out those plates.

And there was one time when Manny traded a grandfather clock for its value in ice cream from the first Canadian importer of Häagen-Dazs. “Best business deal ever for a household with four kids!”

The Difficult Process of Ending Operations

Craftline lasted until 1991, when two hammers fell at once: The Canada-US Free Trade deal (precursor to NAFTA), and the introduction of the GST (Goods and Services Tax). Both hit manufacturers hard. Everyone knew Canada’s furniture industry wouldn’t make it, and despite a valiant effort to keep things afloat, the bank stepped in and forced Craftline into bankruptcy.

By then, Manny was the sole owner. He and Henry had bought out Leonard in about 1975, and Henry got out in the final few years.

It was very upsetting, says my mom, after putting so much of your life, money, time, energy, and creativity into something, and then to have the rug pulled out from under you through no fault of your own.

She worked by his side the entire time. Manny was more philosophical and practical about it. He really didn’t dwell on things. It happened, so it happened. Meanwhile, he had other business ventures and interests. He also took the opportunity to go to Poland, with Freda, for the first time since the war and write his memoir (Carved in Stone: Holocaust Years – A Boy’s Tale).

Personal Challenges

We had one very fine oriental-style grandfather clock for about 40 years until it was consumed by flames in a house fire in 2011. So we all grew up with that wonderful ambient chime every 15 minutes. We’re elated to hear that many Craftline clocks are still working well!

What he enjoyed most about business was always the challenge. Clocks were just the next challenge, having mastered furniture. Lack of experience was never a barrier. He was not motivated by money—he was motivated by trying to make a longshot succeed. Nothing daunted him. Certainly, that attitude came from surviving the Holocaust. Money was fleeting—in a single day, it could be made worthless. And since he’d already been through the worst, no setback was terribly troubling. He also got bored quickly with the routine.

The Legacy of Manny Drukier

It’s extremely heartwarming to hear that you (author) care to research and record the history of Craftline. He’d be gratified to know it! Occasionally, we hear about this or that Craftline clock still standing in someone’s home, and it’s always satisfying to know its chimes are resonating in someone’s life.

Manny had many business ventures over the years, not just Craftline, although Craftline was the constant, and the one that made money. But he also dabbled in real estate, although he found it generally uninteresting (unless he had colourful tenants).

He published two short-lived magazines—a cooking magazine, “à la carte [sic]”, and a literary magazine, “The Idler”. He opened a pub we lived above, also called The Idler, and ran that for 15 years. He became an author and the star of a documentary my husband and I made about his war years called Finding Manny.

Manny was an innovator—if he had a vision, he went for it, and nothing would stop him. Because of the war, his formal education stopped at grade 4, but he was a voracious reader and a lifelong learner. He was a generous mentor and an incurable optimist. He also had a great sense of humor and left us with many useful words of wisdom.

“I’ll leave you with a few gems that seem most apt:

- LIfe isn’t a cafeteria, you can’t always choose what you want.

- Sometimes a kick in the pants is also a step forward.

- Don’t be the schmuck who ends up walking backwards when you’re moving furniture.

- I think I’ve contributed something by my staying alive. (in Finding Manny):

We agree.

The Drukier Family”

That’s the story—more than I ever expected. I encourage you to watch Finding Manny, which explores Manny’s early life, the profound loss of family members during the Second World War, and the horrors of the death camps.

Given the lack of other dedicated online sources, this stands as the most reliable and comprehensive resource currently available on Craftline Industries.

Discover more from Antique and Vintage Mechanical Clocks

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Wh

LikeLike

Wonderful and interesting read. Thanks so much for the article.

LikeLike

Thank you.

LikeLike

I have the same clock as the author’s daughter bought in the 70s, how much could I sell it for?

LikeLike

I have the same clock as the author’s daughter. My I laws bought it in the 70s. How much could it sell for?

LikeLike

As much as I admire the workmanship and the beauty of these old grandfather clocks, unfortunately they have retained little value today. For example the clock pictured came with a house my daughter recently purchased and I know she did not pay over $300 for it.

LikeLiked by 1 person