Honestly, an entire book could be devoted to the topic of dating clocks. Some time ago, I published an article titled “How to Date an Antique or Vintage Clock – Part I,” in which I used specific examples from my own collection.

I’d like to explore this topic further, and this post will discuss additional methods for dating an antique or vintage mechanical clock. While there is no one definitive method for dating an antique or vintage clock, there are often clear clues in some cases and more subtle hints in others that can help pinpoint when a clock was made.

Occasionally, the exact month and year are displayed somewhere on the case, and in other instances, the clock by way of serial numbers, date stamps on the movement, style of hands, spandrels, dial design, case design, and so on, establishes the date to within a certain period.

After 1896 foreign clocks (Europe, England) were mandated to have the country of origin on the case, usually on the dial. Any clock made after that date will have the country of origin.

Duration of manufacture

A bit of research into the history of a clockmaker can help you narrow down the timeframe for dating your clock. For instance, the E.N. Welch Clock Company, an American manufacturer, produced clocks until 1903, when it was acquired by the Sessions Clock Company, which continued making clocks until 1970. The E.N. Welch Clock Company made clocks for a 50-year period until its acquisition by Sessions in 1903.

By 1903 German-based clock manufacturer Junghans was the largest clock maker in the world and continued in its quest to bring more companies into the fold. Gustav Becker, founded in the 1860s, and Hamburg American Clock Company, founded in 1883 were absorbed by Junghans in the late 1920s. Although those companies were folded into Junghans in 1926 the Gustav Becker name lived on for another 9 years.

Clocks with Steel vs Brass plates vs Woodworks movements

Smaller shelf clocks with 1-day (30-hour) wooden movements were produced in fairly large quantities from around 1810 to 1845, after which most clockmakers changed over to brass movements. Wood dials were also popular during this period.

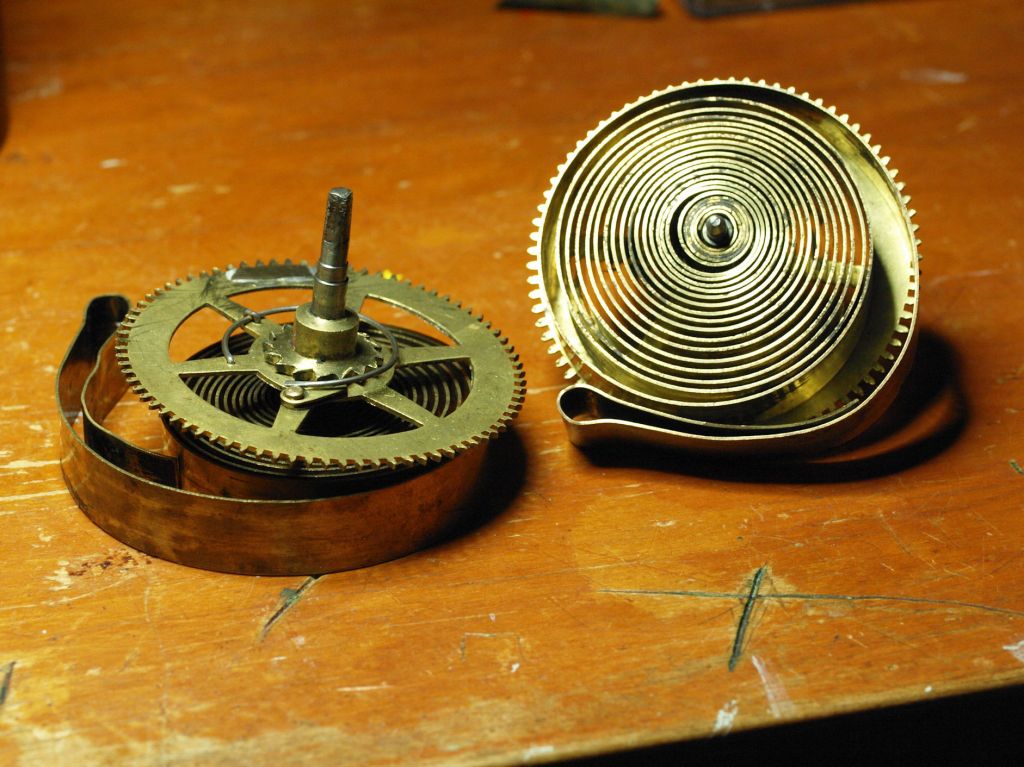

By 1860 iron weights were being replaced by springs as the power source, and smaller clocks, many of them 8-day, were becoming increasingly popular. Early American spring-driven clocks used brass springs (late 1830s) until steel became cost-effective.

This information is important for dating a clock because it highlights key transitions in clockmaking technology and design, which can help pinpoint the era in which a clock was made. For example, the use of wooden movements and wood dials can indicate a clock was produced between 1810 and 1845. The shift from iron weights to springs by 1860 helps us understand why spring-driven clocks became popular, which is crucial for narrowing the period of manufacture. Additionally, the switch from brass springs to steel in the early 1840s can provide a more precise date range for early spring-driven clocks.

Understanding these technological changes allows you to make more informed judgments about a clock’s age based on its features.

During periods when brass was in short supply such as the World Wars (WWI and WWII), makers often made steel plate movements with brass bushing inserts. However, some companies such as Arthur Pequegnat used either steel plates or brass-plated steel plates throughout their operating years (1902 to 1941).

Other clock companies switched to steel as a cost-cutting measure when brass prices were high, not necessarily during wartime.

Screws and nails, chime rods, coiled gongs

In older clocks, nails, and screws were made of iron and hand-forged, with screw heads being slotted. Hand-forged nails can be found in clock cases dating from the earliest examples up to the mid-19th century, after which machined screws and nails started to replace them.

An ogee clock, like this example made by George H. Clark in 1865, was constructed with hand-forged nails.

Robertson and Phillips head screws were introduced in the first part of the twentieth century. Since the Robertson head was invented in 1906 and Phillips screw heads only began to be widely used in the 1930s screws of these types found in older antique clocks are later additions.

Since these screw types were introduced in the early 20th century, their use in a clock that dates from an earlier period suggests that the screws were likely replaced or added during a later restoration or repair. Recognizing these screws helps refine the clock’s dating and can provide insight into its history and any modifications it may have undergone.

The first rod gong, a single striking rod, dates back to patent designation DRGM 108469, granted to Johann Obergfell on December 23rd, 1899. The introduction of the rod gong, as opposed to earlier bell or strike systems, represents a key development in the evolution of mechanical clocks, especially in terms of sound quality and the technology used.

Understanding when this innovation occurred can help date a clock more accurately, particularly those with rod gongs, as it indicates they were likely made after 1899. Rod gongs are typically made from a copper or nickel alloy and are press-fitted into a block.

There are two types of coils: the thick coils, which spiral only a few times and produce a deep, rich tone, and the thinner coils, which spiral many times and often have a higher-pitched, tin-like sound. Thick coils were used well before the mid-1800s. These coils are typically mounted onto a fitting, which is then attached to an iron block. Smaller, thicker coils became more common towards the end of the 19th century.

On the American front, thin wire coils were very common. Some examples had the coil mounted to a dome-shaped base which was said to improve the tone considerately.

Commemorative plaques

Commemorative plaques which display dates are often a good indicator of the age of a clock. However, the clock may have been on a seller’s shelf for years before the date on the plaque. This nevertheless places the clock within a certain range of dates. This photo shows a plaque on a HAC (Hamburg American Clock Co.) time and strike shelf clock.

Type of escapement

Recoil (anchor), half deadbeat, Graham deadbeat, pinwheel, Brocot types are found in older antique clocks while, hairspring, floating balance, lever type escapements are found in newer vintage (less than 100 years old) clocks.

For example, floating balance movements began appearing in mechanical clocks in the early 1950s. The floating balance will tolerate being out of level, unlike pendulum clocks which must be on a level surface, an attractive marketing feature.

This is important because the type of escapement mechanism used in a clock can provide key insights into its age and technological development. Older clocks with recoil (anchor), half deadbeat, Graham deadbeat, pinwheel, or Brocot escapements reflect the horological practices of earlier periods, while newer clocks featuring hairspring, floating balance, or lever type escapements indicate a more modern design, typically found in clocks less than 70 years old.

For example, the introduction of the floating balance in the 1950s was a signifcant advance because it allows for clocks that are less sensitive to being off-level, a feature that made them more convenient for consumers. Recognizing these mechanisms helps in accurately dating a clock and understanding the technological shifts over time.

Style of case

The style of the case, such as ogee, box clock, steeple, cottage, or gingerbread, can help date the clock to a specific period.

The style of a clock case can offer valuable clues about its age, as different case styles were popular during specific periods in history. Here’s a breakdown of some common clock case styles and their associated timeframes:

- Ogee Clocks: These clocks, named for the distinctive curved, “S”-shaped design of their cases, were popular from the early 19th century, especially between 1825 and 1850 but continued to be made into the 1880s. They typically have a simple, symmetrical shape, often with a painted or paper dial, and were mostly made with wooden movements in the early years.

- Box Clocks: This style features a simple, rectangular or square case, often with a hinged door or glass front. Box clocks were common in the early to mid-19th century (1920s to 1940s), with their plain, functional design making them relatively inexpensive to produce.

- Steeple Clocks: Steeple clocks are characterized by their pointed, “steeple” shape at the top of the case. This design became particularly popular from the 1840s through the 1870s. Steeple clocks were typically more decorative and were often used in homes and churches, with some having more ornate carvings or decorative elements.

- Cottage Clocks: Cottage clocks, with their simple and rustic designs, emerged in the mid-19th century, around the 1840s and 1850s. Often smaller in size, these inexpensive clocks were popular in rural homes. They are sometimes characterized by a more casual, handcrafted appearance, with wooden cases and floral or geometric motifs.

- Gingerbread Clocks: This style, which features intricate carvings and decorative elements like scalloped edges, ornate moldings, and small, detailed pieces, gained popularity in the mid- to late-19th century (around 1860 to 1880). Gingerbread clocks are often associated with the Victorian era and were typically mass-produced.

The case style is a strong indicator of the clock’s approximate age because clockmakers and manufacturers often adapted their designs to reflect contemporary tastes. By identifying the specific features of a clock’s case—such as the materials used, shape, and any distinctive decorative elements—you can narrow down the period in which it was made, which can then aid in dating the clock more precisely.

Knowing the period when a case was made provides a reliable indicator of the clock’s age. Although there are earlier patent dates stamped on the movement of this E. Ingraham Huron time and strike 8-day shelf clock, this style of case was made for only 2 years, 1878 to 1880.

Date stamps on movements or cases & searchable databases

Some makers stamp date their movements or display the date elsewhere on the clock case. The Gilbert Clock Company often date-stamped their movements. Sessions put dates on the door labels.

Some makers such as Junghans stamp a date code on their movements. For example, B19 stamped on the back plate of a Junghans movement refers to a movement made in the latter half of 1919.

Serial numbers stamped on movements can be compared to a database to determine the exact year the clock was made. The Ridgeway clock company used 4-digit codes. For example, serial number 4981 refers to a Ridgeway clock made in 1981.

Gustav Becker clocks were made in both Silesia and Braunau factories, both of which produced clocks but each had a unique serial number convention. The serial number on a Gustav Becker clock will give the exact year of production assuming you know where it was made, Silesia or Braunau.

An online databases such as ClockHistory.com provides invaluable information on companies and models made by them, the years the clock company was in business, and how long the company was in operation.

Searchable databases like Mikrolisk, the horological trademark index help date a clock by comparing a trademark. Some companies revise or restyle their trademarks over the years allowing one to date a clock within a certain period.

At Antique-horology.org keywords or text can be used to search trademarks and identify years they were used.

The date 1848 is attributed to the clock above. I arrived at this date because it was made by William McLachlan of Newton Stewart, Scotland. According to an English clock database, Mr. McLachlan was a clock assembler and ran a clock-making business in Newton Stewart until his death in 1848. While the clock could have been assembled as early as 10 years prior, 1848 serves as a conservative estimate.

Other miscellaneous indicators

Plywood began to be used in clock cases starting in 1905. One of the clocks in my collection, a Junghans bracket clock, made around 1913, features a plywood back access door.

Seth Thomas made clocks in marble cases for a short time, from 1887 to about 1895. They also made clocks in iron cases finished in black enamel, from 1892 to about 1895.

Adamantine clocks were most popular through to 1915. Seth Thomas is best known for their “Adamantine” black mantel clocks, which were made starting in 1882. Adamantine is a celluloid veneer, glued to the wood case. Adamantine veneer was made in black and white, and in coloured patterns such as wood grain, onyx, and marble.

Final thoughts

My goal for this two-part article was to provide a broad, generalized overview. Each of the sub-topics mentioned above could be explored in much greater detail, and I hope this serves as a useful reference for some of you. I welcome any corrections to the dates, and if there’s anything I’ve missed or other information that should have been included, please feel free to leave a comment.

As I’ve outlined, there are many ways to date a clock—some methods are quite obvious, while others are more subtle and require a bit of research to pinpoint.

For some collectors and clock fans, dating a clock is crucial, as it adds historical context and value to the piece. For others, however, it may not be as important, especially if the clock serves primarily as a decorative item rather than a functional or collectible piece. In such cases, the aesthetic appeal might take precedence over its exact age.

Discover more from Antique and Vintage Mechanical Clocks

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Very informative post. And as always… I learned new things.

LikeLike

Thank you. As I said one could write a book. I just touched on a few things.

LikeLiked by 1 person