A mechanical clock is more than just a sum of its parts; it is a remarkable machine designed to measure, verify, keep, and indicate time. These devices allow us to measure intervals shorter than the natural units of the day, the lunar month, or the year.

How many machines can you name that run almost as well as they did the day they were built over 100 years ago and still operate exactly as designed? Not many! This enduring functionality is a testament to the ingenuity and vision of their inventors. Mechanical clocks are truly a marvel of engineering!

A True Story

Let me begin with a sad but true story. A few years ago, a friend of my son was visiting our home. He showed an interest in my clock collection, and I was more than happy to answer his questions.

At one point, he asked me how a clock worked. I picked up an American time-and-strike spring-driven movement and explained how the spring provides power, how the wheels transmit energy, and how that energy is released to keep time. He took the movement in his hands, examined it closely, and then, with a puzzled expression, asked, “Where do the batteries go?”

How A Clock Works

But how does this centuries-old invention actually work? Let’s take a closer look at the fascinating inner workings of mechanical clocks and discover how they keep time with such precision and elegance.

Let’s keep it simple by focusing on the Five elements that are required. They are Power, Gears, Escapement, Regulator, and Indicator. Let’s discuss each one.

Power

The power is in your hands. The energy from you is transferred to the mechanical clock when winding it. As you insert the key into a winding point, energy is converted from your hand to the spring or weight.

The spring when fully wound or the weight pulled to its highest point provides the motive power or releases energy through the gears and allows the clock to run for a fixed period of time. Without a source of power, a mechanical clock will not run and a mechanical clock will stop when power is spent.

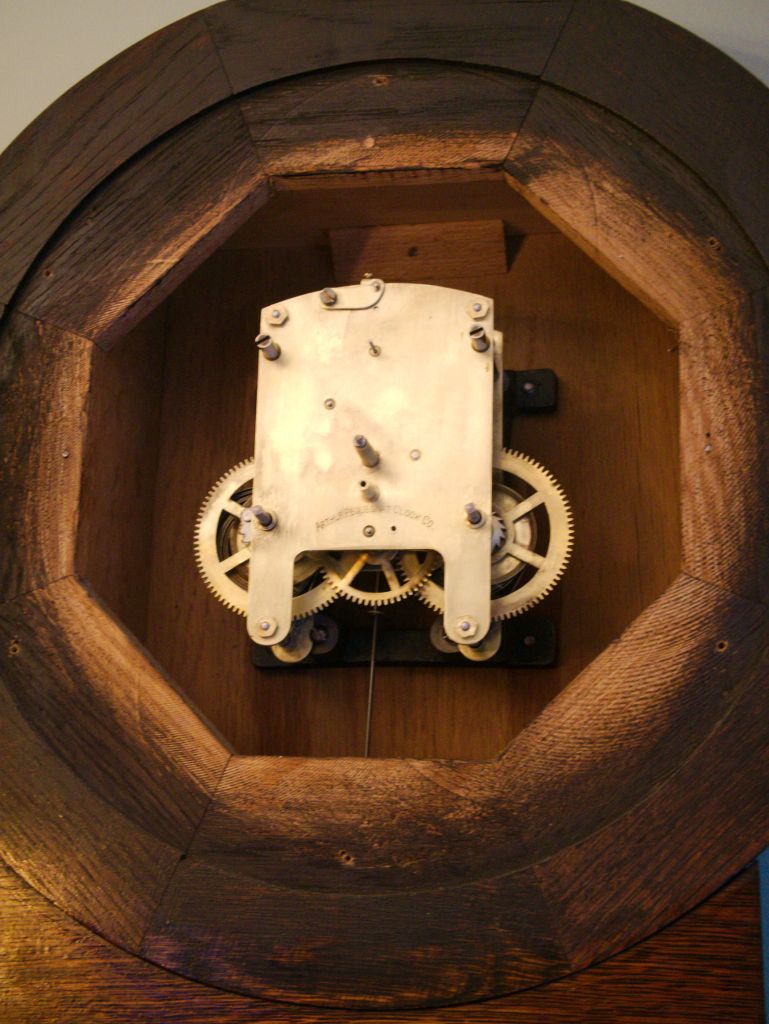

Gears or Wheels

Gears are also called wheels. The wheels have teeth. Each gear or wheel meshes or interacts with the next gear by way of pinions.

Energy is transferred to each wheel through what is called the train and in the process, the subsequent wheels turn faster. The time side gear train, for example, through a series of wheels leads to a wheel or gear called the escape wheel which turns much faster than the main wheel with the spring or weight. But the power that is released through the train must be controlled.

Escapement or Controlled Release Mechanism

The escapement is the last wheel in the time train. It is designed to release the power from the mainspring or weight in a controlled manner.

This is the tick and tock you hear when you are close to a mechanical clock. It is the sound of the verge catching and releasing the teeth of the escape wheel. The tick and tocks transmit an impulse to the pendulum to keep it swinging.

Similarly, the mainspring releases the energy through the gears or wheels on the strike side of a clock by means of a series of levers and pins.

The Regulator

A regulator controls the speed of the clock. An example of a regulator is a pendulum. Generally speaking, a pendulum with a longer rod will oscillate more slowly than one with a shorter rod.

Regulating or adjusting the length of a pendulum will speed or slow down a clock. On the same clock, lengthening the pendulum slows the clock, and shortening the pendulum makes the clock go faster.

Clocks without a pendulum have lever escapements, floating balances, and balance wheels that rely on a coiled spring and are regulated by means of an adjustment dial or lever on the escapement arbour.

Indicator

The indicator is the hands on the dial face. Regardless of the size of the dial, the style of the hands, how numbers are displayed, they all do one thing, tell the time.

The indicator also points to the sound a clock makes at a certain part in the hour whether it is quarterly, the half-hour, or the hour on a bell(s) or chime rod(s).

Synergy

The five elements come together to create synergy—a harmonious interaction of parts that produces a result greater than the sum of their individual contributions. This controlled harnessing of energy is ingeniously designed to make the machine perform one task: tell the time.

I think my son’s friend still wondered where the batteries go.

Discover more from Antique and Vintage Mechanical Clocks

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Hi Ron, Thanks for that. You mentioned elsewhere that the “escapement mechanism” on American clocks are different (and louder) than on non-American. Is it relatively simple (probably not!) to explain how and why? Also, the Regulator in the center top on some clocks: does turning this adjust the length of the pendulum or does it control speed in some more subtle way? Thanks again! And oh, I forgot, where do the batteries go again?

LikeLike

Thanks, David. The loud ticking is the result of a long drop. Some clocks can be made quieter by moving the pallets closer to the escape wheel teeth. American clocks also have larger cases (generally) that act as a soundboard. German, French, and British clocks on the other hand have smaller and better-designed escapements and are generally in more compact cases. American clocks lack the engineering refinement of a German clock but will run well while quite worn. The regulating arbor on the front of the clock case controls the speed by using a small gear to change the length of the suspension spring and in effect make the pendulum longer or shorter. Can’t see where the batteries go but when I do I will let you know.

LikeLiked by 1 person