Some time ago, I discussed clock repair in the old days with a horologist acquaintance who completed work on my 138-year-old E. Ingraham Huron mantel clock in my collection. He had just spoken with an 82-year-old friend who spent most of his life in clock repair, reminiscing about how different things were “back in the day.”

I wondered what he meant by “different.” Were things genuinely better in clock repair back then? Let’s take a step back in time.

Imagine a typical Canadian home in the 1920s or 1930s. In those days, a clock was more than just a decorative piece; it was a vital appliance—just like a refrigerator or washing machine.

For most households, clocks were bought for one simple purpose: to tell time. Often, it was the only timekeeping device in the home, especially for working-class families. And although mechanical clocks were not the most accurate, people did not expect them to be precise to the second. As long as the clock was within a minute or two each week, it was more than up to the task.

These clocks were inexpensive, functional, and built to withstand some wear and tear. My own Arthur Pequegnat “Fan Top” kitchen clock, for instance, was sold for $5 when new in 1912—a significant investment when the average worker earned around $12.75 weekly.

Despite the cost, having a clock in the home was essential for various reasons. When a clock inevitably stopped, it needed a quick and affordable repair, often done by a local tinkerer rather than a professional. This could be a tradesperson like a mechanic or handyman. In rural areas like Nova Scotia, Canada, trained horologists were rare, and even when available, their services could be prohibitively expensive.

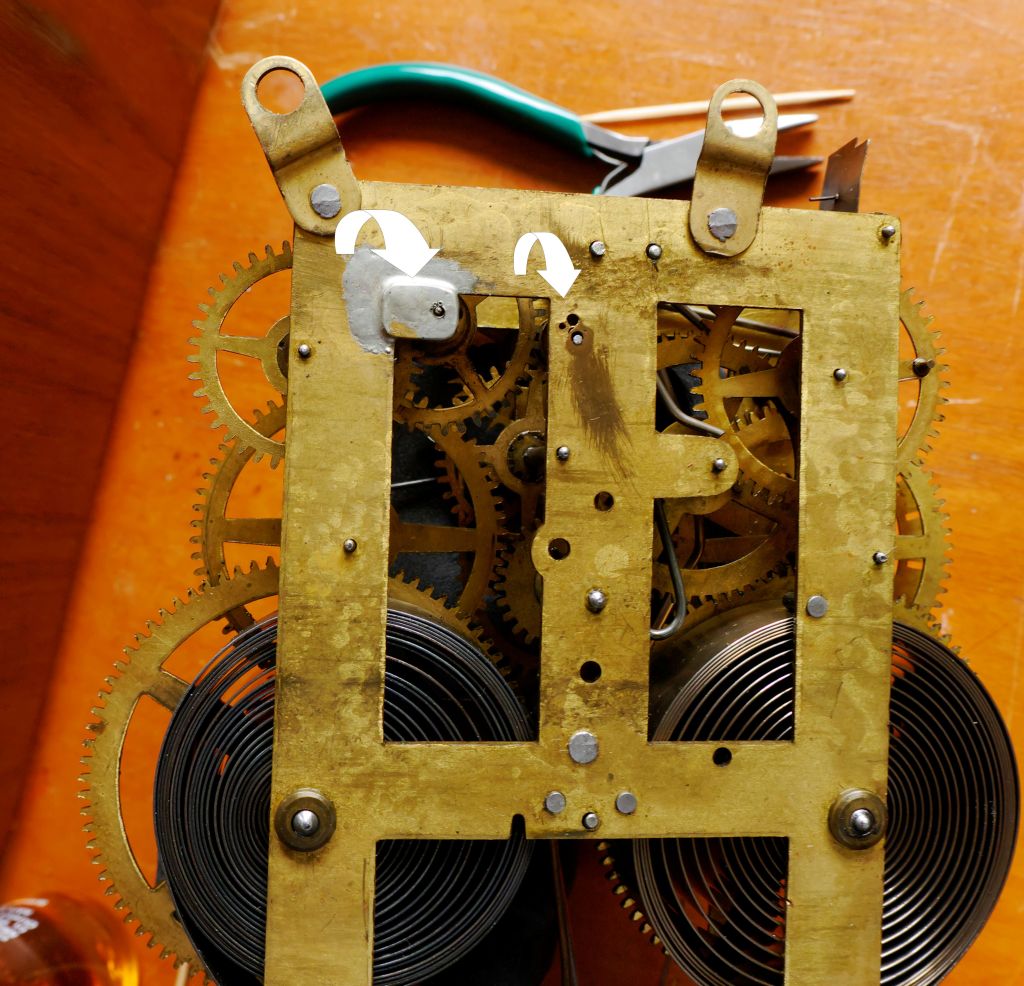

The local “tinkerers” kept neighbors’ clocks running, relying on basic tools found around the house: a hammer, pliers, a punch, a file, and a screwdriver. In those days specialized tools for clock repair were expensive and hard to come by and only a jeweler could afford such luxury. Tinkerers often used improvised methods; for instance, they might close a worn pivot hole with a punch or, by the 1940s, use a soldering gun to attach a brass piece, creating a new pivot hole when needed.

Cleaning solutions were equally unrefined—soaking movements overnight in gasoline, then oiling them with household oils like motor oil. Reflecting on the cleaning methods of those early tinkerers, the use of gasoline and other flammable solvents to clean clock movements stands out not only for its crudeness but for the inherent danger it posed.

Gasoline was relatively inexpensive and readily available, which made it an attractive option for a low-cost, no-frills clock cleaner. However, using such a volatile substance to clean intricate brass and steel components was not without significant risk.

The workspace for these repairs was often an unheated shed, garage, or basement without proper ventilation, increasing the risk. In these confined spaces, the fumes would linger, building up to dangerous levels. One careless move, and the result could be disastrous, not only for the tinkerer but for anyone in proximity.

The Quick Fix

“Quick fixes” were typically short-term and would eventually lead to further repairs. Still, the customer was satisfied if their clock came back ticking, and they paid only a nominal fee for the service.

These short-term fixes often involved unconventional methods. For instance, rather than replacing worn bushings—small bearings that support moving parts—a tinkerer might use a punch to “close” a pivot hole by pushing the metal back into place. This would hold the pivot for a while, but it also introduced more wear, which would lead to increasingly frequent repairs as the pivot wore down the surrounding material. Other techniques included using adhesives, shims, or rudimentary re-soldering to hold parts together temporarily.

For lubrication, household oils like 3-in-1 were a staple, though they were not formulated for delicate clock movements. These oils would initially help gears move smoothly, but over time, they could become sticky, causing grime to build up and eventually slowing the movement once again. Each time a clock came back for a fix, the tinkerer would apply another short-term solution, usually at little or no cost to the customer, who was primarily concerned with keeping the clock functional.

The cumulative effect of these fixes meant that many clocks would eventually suffer irreversible wear. The gears and pivots would lose their integrity, requiring a complete overhaul if they were to be restored to original condition.

However, it’s worth mentioning that these clocks were not seen as heirlooms or prized possessions; they were utilitarian items. For customers, the reliability and exact timekeeping ability of the clock was not as important as affordability and functionality—if it ticked, it was good enough.

The Emergence of the Electric Clock

In the 1930s, synchronous electric clocks began to replace mechanical ones in homes with electricity. However, in many rural areas, families continued relying on their mechanical clocks, repairing them as needed until electric clocks eventually phased them out.

While many of those old clocks were abandoned, some became cherished family keepsakes passed down through generations.

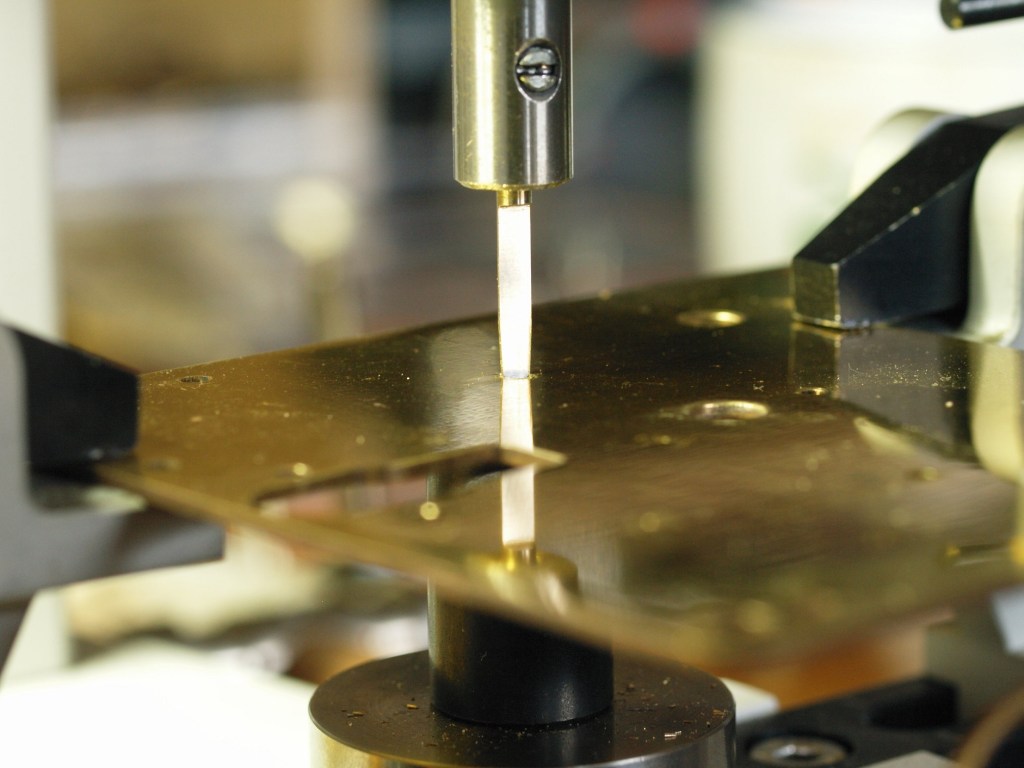

Today, antique clocks hold a different status; we value their craftsmanship and history. When they need repairs, we use all manner of specialized modern tools—bushing machines, broaches, spring winders, and lathes—to restore them with precision. The result is a repair that lasts, leaving our clocks “better than ever.”

Remembering past tinkers

Yet, it’s important to remember the tinkerers of the past. In their time, they provided an essential service, keeping communities running on time. While we might wince at some of their makeshift repairs and call them “butchers,” those tinkerers were problem-solvers.

Speaking with my friend the horologist helped me better appreciate the humble, practical repairs of the past and the indispensable role these community tinkerers played.

When I encounter a clock with a “homemade” repair, I assess the quality of the work. If the repair, however crude, has stood the test of time, I often choose to leave it as is, recognizing it as part of the clock’s unique history.

Modern Repairs

Clock repair today is a world apart from the makeshift methods used by tinkerers of the past. Modern horologists have access to advanced, highly specialized tools—bushing machines, ultrasonic cleaners, spring winders, precision lathes—that allow them to restore and even improve upon the original functionality of antique clocks. This level of precision would have been unimaginable to the early tinkerers who often relied on a handful of common household tools, improvising as they went along.

For them, a hammer, screwdriver, file, and eventually a soldering iron were the core of their toolkit. These tools were not intended for delicate clockwork but were adapted out of necessity, resulting in quick fixes rather than long-lasting repairs.

The philosophy behind clock repair has also evolved dramatically. Modern repairs focus on preserving the integrity of the clock, respecting the craftsmanship of its original makers. Each repair is a detailed process, and the goal is longevity. Modern techniques consider the clock’s historical value, aiming to keep its character intact while ensuring that it runs smoothly for years. This contrasts with the approach of early tinkerers, who were less concerned with historical value and more focused on getting the clock running again as quickly and affordably as possible.

Materials and cleaning methods today are specifically formulated for delicate clockwork. High-quality brass bushings, synthetic clock oils, and non-flammable cleaning agents protect the movement and prevent unnecessary wear. In the past, tinkerers often resorted to materials that were easily accessible but not ideal for clock repair. These methods may have restored basic function, but they often led to increased wear over time, necessitating further repairs and eventually compromising the clock’s condition.

In the early 20th century clock repairs were practical, unrefined, and performed with whatever was on hand. On the other hand, modern horologists have become part conservators, honoring the original makers by using high-quality techniques that preserve each clock as a historical artifact.

Modern horologists can train extensively, gaining a nuanced understanding of clock mechanics and restoration practices. Tinkerers, on the other hand, were often self-taught, relying on trial and error, observation, or advice from others. Many of them fixed clocks in their spare time, making do with limited resources and no formal training. Their skills were functional, focusing on keeping clocks ticking within the practical constraints of everyday life.

Today, when a clock is restored, we think of it as honoring history, a far cry from the “just make it tick” mindset of the past. Both approaches, however, share a common thread: a dedication to keeping time alive.

Discover more from Antique and Vintage Mechanical Clocks

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

👍🌞

LikeLike

Hello Ron.

The first clock I tore down and cleaned and repaired over a year ago now was a time only Par Aro. One of the bushings was need of replacing but I wasn’t yet equipped with an assortment of bushings etc. So I simply marked the centre axis’ of the bushing then filled it with brazing rod in my welding shop. Re drilled the bushing and put the k cement back together. This clock continues to run to this day. On the topic of oils, I recently read in a reputable horology book that Mobil 1 synthetic oil is a perfect alternative to otherwise expensive clock oil. This lead me to adopt the philosophy that not every repair procedure needs to be a NASA spacewalk.

LikeLike

On the topic of oils, it’s interesting to hear that Mobil 1 synthetic oil was recommended as a suitable alternative for clock oil. It’s a reminder that sometimes, less expensive, widely available products can do the job just as well as specialized ones. A practical, “keep it simple” approach to repairs is often the best way to go. Not every repair needs to be a complicated, high-tech procedure; sometimes the right solution is the simplest one that works. And if the simple solution works and holds over time it was probably the best one.

LikeLike

Thanks Ron, Good insight into how repairs done decades ago. A servicing today done using these methods would be, as you pointed out, poor workmanship. Can respect though back in the day, name of game was getting clock back in service.

LikeLike