A 400-day clock, also known as a torsion clock, is a type of mechanical clock designed to run for about a year (400 days) on a single winding. It features a unique suspension system, where a rotating pendulum or torsion spring controls the movement. The clock’s long running time is achieved through a very slow, consistent release of energy from the mainspring, and the mechanism is typically enclosed in a glass dome for display. Though not particularly accurate they are fascinating to watch.

Years ago my daughter gave me a Horolovar guide as a Christmas gift. Any horologist will agree that the Horolovar guide is an indispensable guide when working with 400-day clocks.

It is not a manual one opens up regularly but when working on 400-day or anniversary clocks, as they are often called, it is an absolute necessity.

The guide was last published in June 1991, and I believe little has changed since then, as I’m unaware of any mechanical anniversary clocks still in production today.

Using the Manual

My daughter was in the midst of moving across the country when she unknowingly overlooked the locking mechanism on the 400-day clock she had received as a gift a few years ago. Upon unpacking it, she found that the suspension spring had snapped. While a snapped suspension spring can’t be reused, it can be easily replaced.

400-day clocks require very specific suspension springs, ones specially designed for each of the many dozens of manufacturers in the past 100 years. Install a suspension spring with an incorrect thickness and length and you are asking for trouble. The correct spring for the make and model of the clock will ensure a smooth-running anniversary clock that will operate for many years.

On the positive side, these clocks run so slowly at 8 beats per minute that it is rare to have worn pivots and bushing holes.

Back to the clock in question. It is a Kundo anniversary clock made in the 1950s. According to the Horolovar guide, it is model 1371. Model 1371 tells me that the thickness of the suspension spring is .081 mm or .0032″. I’ve worked on similar models before and had some leftover Horolovar suspension springs of that size.

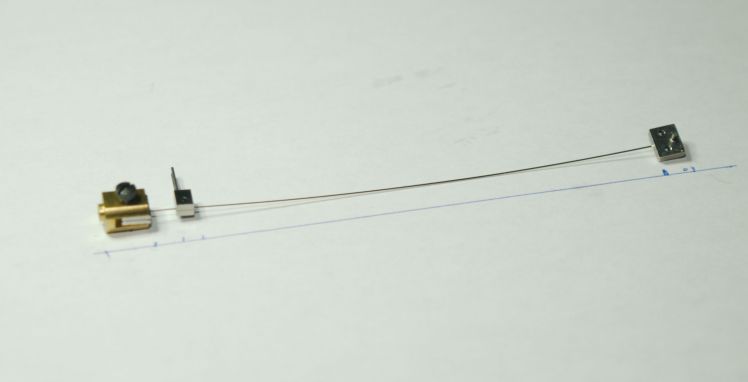

This is essentially a one-hour job. There are two blocks, one at the top and one at the bottom. Carefully unscrew the blocks, ensuring the spring doesn’t become bent during the process (the small screws can be tricky to loosen). Once the blocks are removed, insert the suspension spring and tighten the screws. After securing the blocks, the manual will indicate where to attach the suspension fork.

Install the assembly onto the clock by attaching the top block with a screw that threads into a hole and hooking the bottom block onto the pendulum but your work is not finished.

Now comes adjusting the beat and regulating the clock. There is a bracket above the suspension spring assembly that can be turned slightly (it is a friction fit) in either direction to correct the beat. I set the beat by ear and eye but there is a beat setting tool that can be purchased from a clock supplier if you plan to work on a lot of these clocks. In any event, a beat amplifier is an absolute must.

Most 400-day clocks run at 8 beats per minute. Mine runs slightly faster at 9 beats per minute, but this can be adjusted using the dial-type speed regulator at the top of the four weights. While a clock running a bit fast might seem negligible, over the course of a year, it can accumulate into a significant difference of minutes or even hours. As anyone familiar with these clocks will attest, they are not known for their precision in keeping time.

Can you install a new suspension spring without the Horolovar guide? Yes, but you’ll need to research the correct suspension spring thickness for that specific model and use the old assembly as a template.

That said, it’s much easier to simply buy the guide—it eliminates all the guesswork.

Discover more from Antique and Vintage Mechanical Clocks

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

My Kundo runs too fast with a new .0032 spring and the speed regulator maxed out. May I use a weaker spring to adjust and is a weaker spring larger or small (.0030 or .0035)?

LikeLike

Hi and thanks for your comment. If you have a Kundo Standard which is the taller one, the correct spring is .0032″. If you have a smaller version of a Kundo, the Junior, the spring is .0023″. If you used the correct spring and maintained the exact distance between the upper and lower blocks your clock should more or less keep decent time. So, if the suspension spring is the exact length and thickness and your clock runs too fast, is it in beat? It should run at 8 beats per minute. To put the clock in beat, ensure that the pendulum overswing in both directions is equal. A healthy rotation should be 270 degrees or more of swing.

I find that it is very important to have the Horolovar manual particularly if you plan to work on more than one 400 day clock. The manual contains exact suspension spring templates for each 400-day clock in production for the past 100 years.

Having said all that, 400-day clocks are terrible timekeepers and if you can get yours to within 5 (plus or minus) minutes per week you are doing well. In addition, most of the mainspring’s power is released when fully wound. The clock will slow down as the mainspring unwinds and therefore will run slower.

Check this out first before you experiment with a thinner spring.

Hope this helps.

LikeLike

Thanks for your quick response. I have several Anniversary clocks and made it a hobbie to restore them. The “Horolovar 400 Day Clock Repair Guide” is a staple and couldn’t do any repairs without it. FYI- I have completed all the usual as you suggested and hence prompted my contact. I’m really at a lose with this unit. Next I’ll try a stronger suspension spring.

LikeLike

Not a thicker spring but a thinner one. The “rule of thumb” is that a 0.0001 inch change in spring thickness will give you 4 minutes per hour of rate change. A thicker spring will speed up the clock, a thinner one will slow it down. You could also have fluttering and if so, resetting the forks (straighter and higher) will have an effect.

Ron

LikeLike

Ron: One last question please. Went down to .0025 suspension spring but now have fluttering. What causes this and how do I rectify.

LikeLike

Sometimes the anchor bounces enough for an escape wheel tooth to leave the locking face and momentarily touch the impulse face. Too much bounce can lead to loss of impulse or fluttering. Typically, the guide is the “suggested” location of the fork, but you should try moving the fork up the suspension spring towards the top block no more than 2 millimeters or so. Beyond that, I don’t know much more I can suggest.

Ron

LikeLike