Almonte, Ontario, (Canada) is a town that practically invites you to slow down and explore, and that’s exactly what my wife and I did one afternoon in September. In fact, it is called “The Friendly Town”. We drifted from one antique shop to another, discovering all sorts of curiosities. But in one store, I found something that stopped me in my tracks—a stately Waterbury time and strike mantel clock. It felt like uncovering a hidden story, and I couldn’t resist bringing it home.

I was drawn to the open escapement and porcelain dial—features that are relatively rare in a common American clock.

At first glance, it looked intact, but after posting the clock on a popular clock collectors’ website, I was informed that the case appeared to be missing the lower parts of the columns. I asked the poster to supply a photo for comparison. In the meantime, I carefully examined the case myself and did not find any anchor points or residual glue traces that would suggest something had originally been attached there.

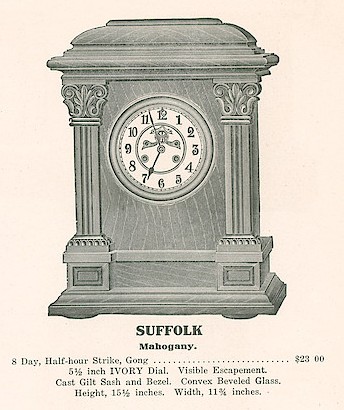

However, further research revealed that there were indeed trim pieces under the columns. This photo, taken from the 1909–10 Waterbury Clock catalog, shows the complete clock. You will note that in 1909–10, the clock was listed at $23.00, slightly more than a typical middle-class worker’s weekly wages in 1910.

The clock is called the “Suffolk”, as shown in Tran Duy Ly’s Waterbury book on page 270 (and the catalog photo above). It is cased in Mahogany, has an 8-day movement, and has a half-hour strike with a coiled gong. It has a six-inch “ivory” (porcelain?) dial with spade and spear hands, and a visible or open escapement. It features a cast gilt sash and bezel with convex beveled glass. The clock is tall at 15 1/2 inches and is 11 3/4 inches wide with wooden biscuit feet.

As an aside, Waterbury also produced a Suffolk model in 1891, which is entirely different from this clock.

The poster said that it is also shown in the 1915 catalog. The patent date on the movement plate is September 1898, so it is quite possible that Waterbury offered the movement for this and other models for a number of years.

When I first looked over the movement, I could see it had been well cared for, still showing a bright, clean finish. But then I noticed something odd: the pendulum was hooked directly onto the crutch. That explained everything—of course, the clock wouldn’t run! It was likely this simple issue that led the seller to list it ‘as is,’ and therefore at a better price.

While trying to think of a way to make a new suspension spring and rod, I thought, why not check the bottom of the case? Sure enough, the original suspension spring and rod had been tucked into a crevice at the inside bottom of the case.

After installing the suspension spring and rod, I wound the movement, gave the pendulum a gentle push, and to my relief, the clock sprang to life. I’m holding off on letting it run too long until I oil the pivots. Once that’s done, I’ll let it run for a while to see if it can make a full 8-day cycle. After that, it will be set aside for proper servicing.

Despite the missing lower trim pieces and the slight chipping around the number 12 on the porcelain dial, it remains a very nice clock and is reasonably well-preserved.

From the tucked-away suspension spring & rod to the moment the pendulum first swung, it reminded me how even the simplest details can make all the difference in getting a clock to run. While it will eventually need a full servicing, seeing it come to life again was a rewarding reminder of why I love collecting and caring for these fascinating pieces of history.

Discover more from Antique and Vintage Mechanical Clocks

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

What an excellent article. I could feel your joy and enthusiasm in this great find. The Ottawa Valley is full of hidden treasuresâ¦..

>

LikeLike

There are a lot of subpar old clocks in antiques stores generally, and some, like this one, are a rare find.

LikeLike

i have inherited a clock similar to this one. its great. I have noticed the hole above 12 oclock and i dont know its purpose. do you? i have adjusted the clock fast/slow using the threaded nut at the end of the pendulum

not sure what other adjustment or winding could be needed at the top of the movement

LikeLiked by 1 person

The little hole above the 12 is a regulator to adjust the time, to make the clock slower or faster. It requires a double ended key, one end to wind the clock and the other to insert into the small hole to turn a gear which regulates the time. If you look closely to can see the tiny letters “s” and “f” for fast and slow. It looks like this https://timesavers.com/i-8948322-6-000-brass-double-end-key.html

LikeLike