When discussing American clocks, the name Elisha Manross might not come to mind as readily as prominent makers like Seth Thomas, New Haven, or Waterbury. However, Elisha Manross (1792–1856) played a pivotal role as a pioneer in the development of Connecticut clockmaking.

In 1812, at the age of 20, Elisha Manross, along with John Cowls, opened a shop in Bristol, Connecticut. Initially focused on woodturning, Manross did not set out to be a clockmaker. In 1825, he began making clock parts for other clockmakers. By 1835, Bristol was home to over a dozen clock factories producing woodworks clocks, and that year, Manross started producing clocks of his own. The 1837 depression marked the decline of wooden movement clocks and the rise of brass movements, particularly those invented and produced by Jerome1.

In the early years of clock production, materials were limited, and brass was commonly used for most components.

Brass mainsprings are exceptionally rare, and a clockmaker could easily go their entire career without encountering one. This is because brass mainsprings were only used for a brief period in American clockmaking history. Although carbon steel springs were used in Europe as early as the 1760s this technology was not used in America until the late 1840s.

From 1836 to 1850, brass was relatively inexpensive and readily available as a mainspring material due to the high cost of steel at the time. Brass is certainly not the best material to use as a mainspring since it is not as strong as steel and it loses its elasticity over time.

In 1847, the tempered steel mainspring, designed for everyday clocks, was introduced. This innovation quickly rendered brass mainsprings obsolete, relegating them to a niche chapter in horological history.

It is common for 30-hour time-and-strike Gothic steeple clocks, like this one by Elisha Manross, to feature steel mainsprings. Why? Because the original brass mainsprings broke and were replaced. The fact that this clock retains its original brass mainsprings in excellent condition suggests that it has led a relatively gentle life despite evidence of other repairs made to the movement over the years.

While some might consider replacing the brass with steel mainsprings, my priority was to maintain the originals. These brass mainsprings represent a significant chapter in the history of American clockmaking and deserve to remain in the movement where they belong.

The photo above shows a collection of clocks I purchased as a batch for $20 several years ago with Manross clock on the far right. My goal was to salvage parts and restore the best clock in the group as a learning project, focusing on returning it to working order and enhancing the case’s appearance. The only one worth preserving was the Elisha Manross steeple clock, and even then it needed some significant work.

The case was in poor condition, and after removing the dial face, it became evident that the clock hadn’t run in many years.

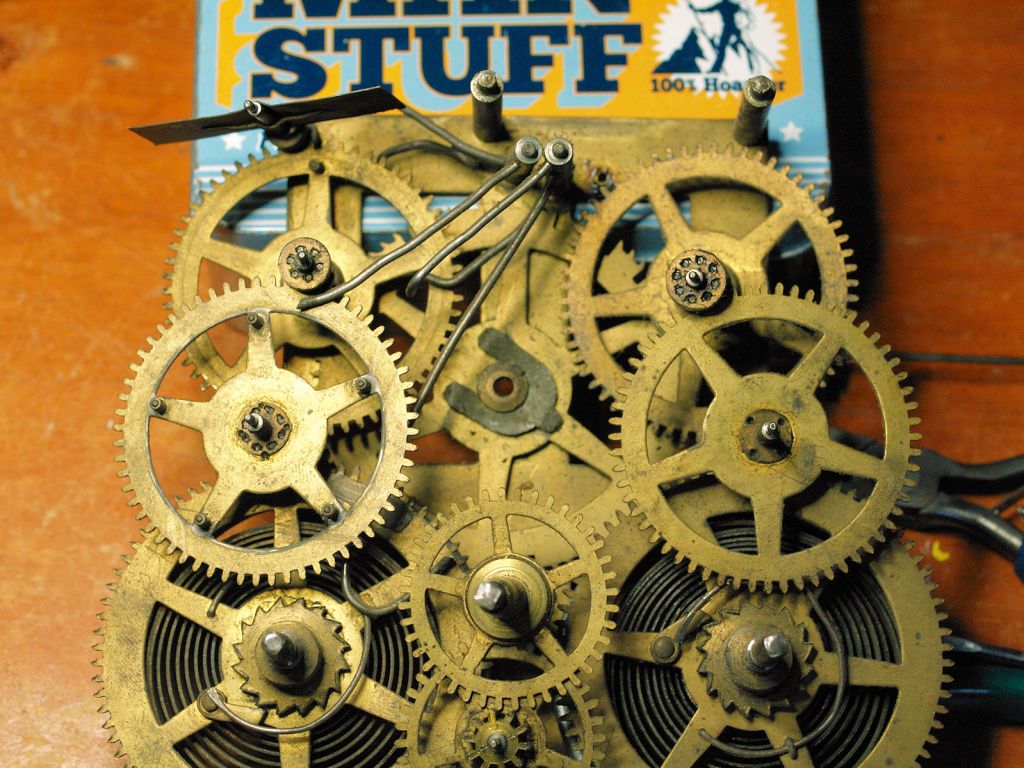

Although I was pleased to find the brass mainsprings in excellent condition, several other issues with the movement became apparent during its disassembly.

Subpar repairs

It’s not unusual for everyday clocks to bear signs of subpar repairs over the years, and this clock is no exception. For most households, having just one clock meant a quick repair was essential to get it running again. Often, the solution was to take the clock to a tinkerer who used whatever methods were available to restore its functionality.

The movement shows numerous punch marks, a result of an old practice used to close pivot holes. While this method was once a common, cost-effective solution for quick fixes, it is now widely discouraged.

Backyard mechanics often relied on such shortcuts for short-term effectiveness.

The main wheel has six teeth replaced with brass, and solder around the insert indicates a much later repair. While the repair is functional, it’s clear the repairer prioritized utility over aesthetics.

As anticipated after years in storage, the movement was dirty and gummed up. Apart from worn teeth on the two main wheels, the count wheel, and both ratchets, the remaining wheels, and lantern pinions were in good condition. Although the levers had been bent by various repairers over the years, they functioned properly after cleaning and required no additional adjustments.

New bushings were installed only on the pivots with considerable wear, while the round punch-marked holes were left unchanged.

Issues with the Case

Now, onto the case. The most notable issue was the missing right steeple and base. Since I wanted to display the clock, it wouldn’t look complete without that feature. Using a softwood block and veneer, I set about crafting a new steeple base.

Using a wood lathe, I crafted a new steeple and did my best to match the steeple on the left.

A sliver of veneer was missing from the left column near the base, which I repaired with a small section on hand. In addition, a piece was missing from the right rear base, which I also replaced. Other than a thorough cleaning with soap and water, the veneer was left untouched, except for applying a thin protective layer of traditional shellac.

An interesting feature is that the grain of the veneer runs vertically and parallel to the long direction of the case sides. Most steeple clocks at the time and those that came later from various manufacturers had horizontal grain on the columns.

The dial face was left as is, but the hands were replaced, as I only had one original slender spade hour hand.

The tablet likely featured reverse-painted artwork by Fenn perhaps, but at some point in the clock’s history, it was replaced with clear glass. A decorative tablet would have enhanced the clock’s appearance.

Inside the case, the label though yellowed with age, is in excellent condition, clearly displaying the maker’s name and the location, Bristol, Conn., where the clock was made.

The clock features a coil gong, as is typical for this era, but based on similar clocks, it seems to be missing the bell cover over the gong mount.

Working with Brass Mainsprings

Working with brass mainsprings requires special care, as they are more delicate than their steel counterparts. Unlike steel springs, brass mainsprings cannot be stretched out for cleaning.

After removing them from the ultrasonic cleaner, I carefully dried them using strips of terry cloth, working the cloth into the coil as close to the center as possible.

Although the movement is now functional, the strike side works well and the case is presentable, I won’t be running this clock regularly to avoid damaging the mainsprings.

In conclusion, this clock has undergone some restoration, preserving its original components where possible while addressing necessary repairs. Despite its wear and modifications over the years, it remains a testament to the craftsmanship of its time, and with careful attention, it continues to hold both functional and historical value.

- NAWCC, various articles on Elisha Manross ↩︎

Discover more from Antique and Vintage Mechanical Clocks

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Morning, Ron…

Wow – this was indeed a very challenging project, and you’ve done a marvelous job!

I wish you would feature these projects on a YouTube channel so that we could really see & even better appreciate your skills.

Thanks for another very interesting article, and holiday wishes your way…

LikeLike

I’ll look back on my photos and see what I can do.

LikeLike