The Seth Thomas Clock Company, renowned for its long history dating back to the early 19th century, produced a variety of clock movements over the years, and among them is the Type 89 movement found in this clock.

Despite the absence of a specific year stamp, the clock’s design and construction suggest a manufacturing date in the mid to late 1930s. Upon initial inspection, it was evident that the clock was not functioning, a common issue with old clocks that have not run in years.

Typically, clock movements face challenges related to low power output caused by wear and tear over time. The gradual deterioration of clocks during years of operation is often attributed to factors such as dirt accumulation, inadequate lubrication, and the lack of proper adjustments.

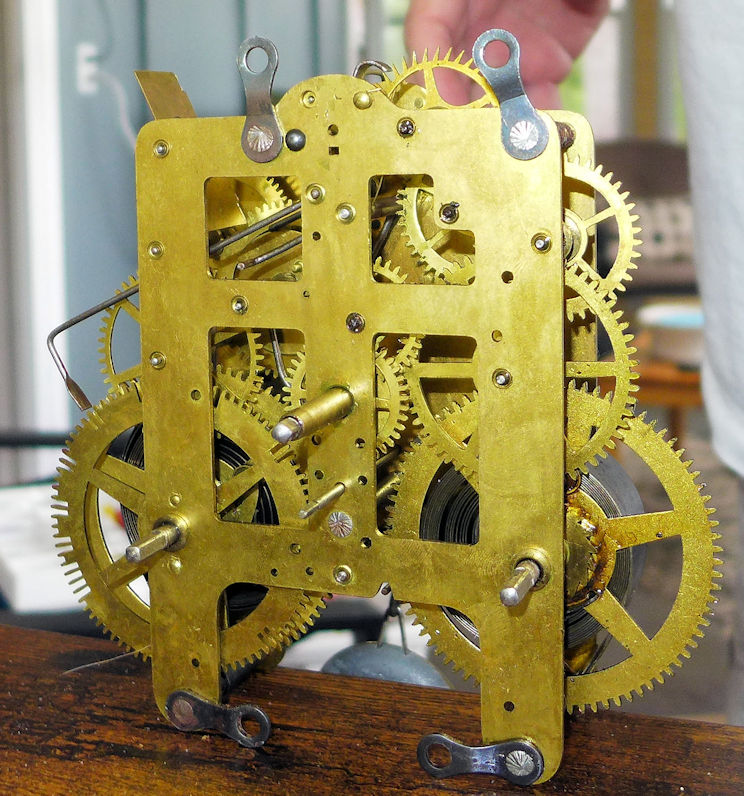

Although dirt accumulation can persist in a movement, causing friction and wear, I decided to see if I could get the clock to run. The process involved removing the hour and minute hands, releasing four screws securing the movement to the front of the case, removing the strike block, and taking the movement out of its case.

An initial inspection revealed no visible issues with either the time or the strike side. Both mainsprings were found to be wound tight and seemingly ceased, likely due to the accumulation of glue-like dirt between the coils that will prevent the clock from running.

To reduce tension on the mainsprings and provide the necessary energy for the clock to start running, an unwinding of the mainspring was performed using a let-down set. Oil was also applied to the pivots, as a temporary solution. Mixing new and old oil is never a good idea as a harmful abrasive paste is produced that could accelerate wear on the pivots and bushing holes. The plan, therefore, was not to run the clock for an extended period but merely to see if it could run.

While relaxing the mainsprings enabled the movement to run strongly, an issue persisted on the strike side, necessitating further investigation. Despite this, no major issues were anticipated, and the next steps will involve disassembly, thorough cleaning, any remediation, reassembly, and testing.

But first, let’s look at the case.

The case

This clock caught my eye at a thrift shop in Renfrew, Ontario, Canada, primarily due to its attractive appearance with what seemed to be rosewood veneer. Intrigued and encouraged by the reputable Seth Thomas trademark, I decided to make the purchase, especially given the appealing price.

However, upon closer inspection at home, I discovered that what I initially believed to be genuine rosewood was actually a thin layer of faux wood wrapping, and to my disappointment, some of it was peeling off in a couple of very visible areas, the worst by the bezel catch.

There might be speculation about whether the movement was reinstalled in a newer case, but my inclination is that this is how it originally left the factory. What the Seth Thomas company might have considered new and improved and would likely fool most consumers was but a cheap imitation.

It is clearly a cost-cutting measure rather than a later modification. Many clock companies faced financial difficulties during the Depression Years of the 1930s, leading them to seek cost-saving measures but honestly, this discovery is rather disheartening.

Nevertheless, the clock holds value because of the movement, which still has many years left. Join me later as we dismantle the clock movement and address any required repairs.

Discover more from Antique and Vintage Mechanical Clocks

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You must be logged in to post a comment.